"To whites every black holds a potential knife behind the back, and to every black the white is concealing a whip." -- René Ricard, "The Radiant Child," 1984

Do you remember the moment in your childhood when you woke up to the dangers and injustices of the adult world? In the life Jean-Michel Basquiat, an American artist of Haitian/Puerto-Rican descent, that moment -- in which he glimpsed the hidden knives and whips -- stretched from his troubled early teens until his death at the age of 27 in 1988. Money, fame and drugs never dimmed the visions of racial injustice and historical abuses of power that both haunted him and fueled his imagination. Jean's sustained adolescent rage became the engine of his bracingly original art.

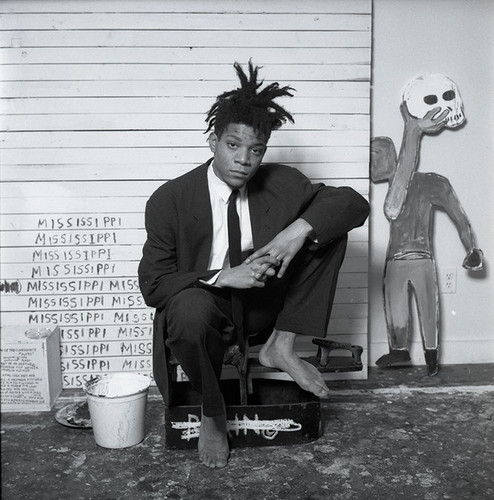

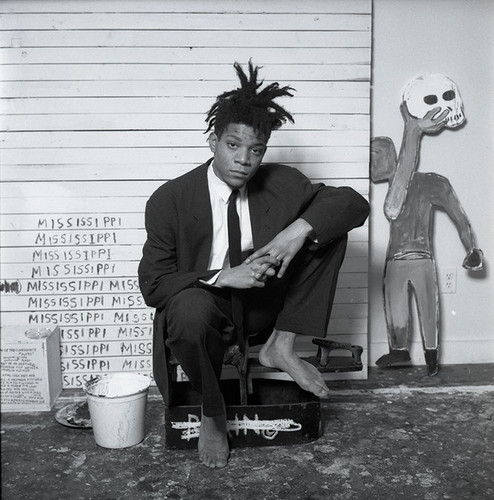

Jean-Michel Basquiat in 1988:Photograph by Dmitri Kasterine. Website: www.kasterine.com. Collection of the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery, Washington, D.C.

Jean-Michel Basquiat in 1988:Photograph by Dmitri Kasterine. Website: www.kasterine.com. Collection of the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery, Washington, D.C.

To cope, and to assert his individualism, Basquiat developed an aesthetic parallel universe with its own impenetrable language of words, signs and symbols. In the words of Marc Mayer, the Director of the National Gallery of Canada, Basquiat "speaks articulately while dodging the full impact of clarity like a matador." An auto-didact whose work parodies and subverts education and history, Jean-Michel Basquiat was the greatest outsider artist of the 20th Century.

Since his death, the art market has increasingly anointed him as one of its greatest insiders. Thousands of artists, would-be-artists, and poseurs have tried to emulate his trenchant precocity, and the results have been predictably lame. Basquiat's prickly intelligence is hard to match, and the esoteric poesia of his finest works is impossible to imitate.

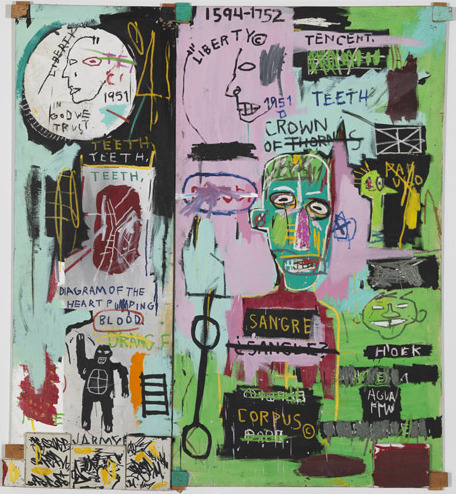

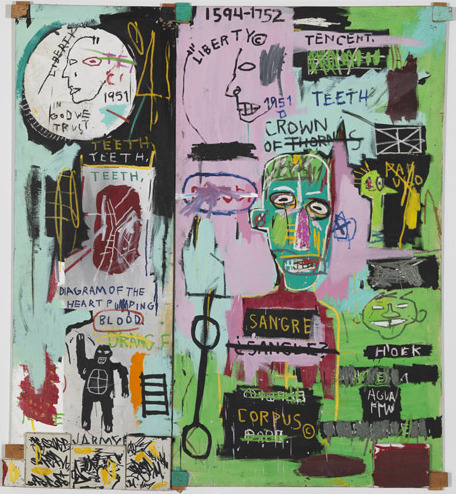

Jean-Michel Basquiat. In Italian, 1983. Acrylic and oil paintstick on canvas with wooden supports and five smaller canvases painted with ink marker. Two panels: 88 1/2 x 80 inches overall (224.8 x 203.2 cm). © The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat/ADAGP, Paris, ARS, New York 2013. Courtesy Gagosian Gallery. Photography by Robert McKeever.

Jean-Michel Basquiat. In Italian, 1983. Acrylic and oil paintstick on canvas with wooden supports and five smaller canvases painted with ink marker. Two panels: 88 1/2 x 80 inches overall (224.8 x 203.2 cm). © The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat/ADAGP, Paris, ARS, New York 2013. Courtesy Gagosian Gallery. Photography by Robert McKeever.

At Gagosian Gallery on West 24th Street in New York, an exhibition of over fifty works includes Basquiat's "In Italian," a quasi-religious diptych which displays an inflamed, contrarian and ultimately indecipherable commentary. It is worth commenting that this vital painting is now 30 years old: three years older than Basquiat was when he died of a drug overdose.

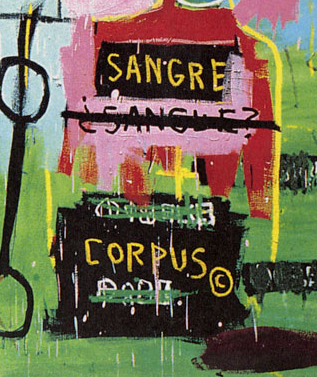

The title of the work offers viewers a suggestion -- that the painting is "In Italian" -- but there are several languages required to "read" the image. Basquiat often included words in his paintings and "In Italian" does have a single Italian word -- "SANGUE" (blood) -- which has been crossed out and replaced by its Latin counterpart: "SANGRE." There are also phrases and words in English, a mangled Italian name -- is it Paulo? -- and one word each in Spanish (AGUA) and Dutch (HOEK). So, inquiring visitors to Gagosian Gallery might start by asking: "Why the reference to Italian?"

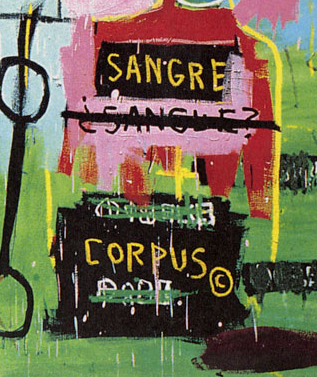

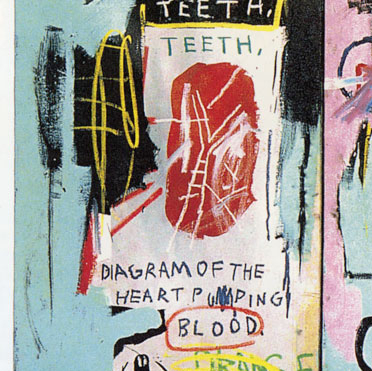

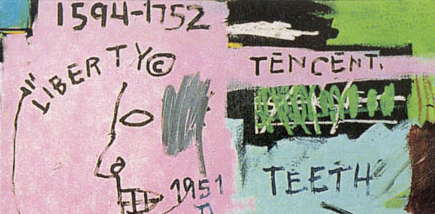

A detail of Jean-Michel Basquiat's "In Italian." © The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat/ADAGP, Paris, ARS, New York 2013

A detail of Jean-Michel Basquiat's "In Italian." © The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat/ADAGP, Paris, ARS, New York 2013

Italy and Italians played a major role in Jean's short career. The Italian Neo-Expressionist painter Sandro Chia was an early advocate for Basquiat's work, and helped introduced Jean to a dealer who had recently moved from Rome to SoHo: Annina Nosei. Basquiat later became friendly with artists Francesco Clemente and Enzo Cucchi, and his first one-man show -- "Paintings by SAMO" -- was held at the Emilio Mazzoli Gallery in Modena in May of 1981. Basquiat, who did not keep track of how many works he gave to Mazzoli, later told friends that the dealer had gotten a "bulk deal" and had ripped him off. On his second trip to Italy some years later Basquiat was detained by Italian customs officials before his departure, as the much wiser artist was carrying roughly $100k in cash, a sum they couldn't believe a young black visitor had earned simply by selling paintings.

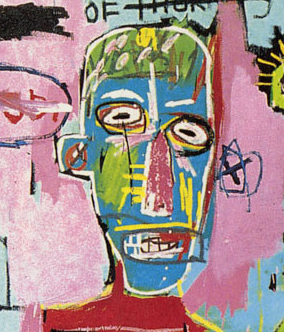

A detail of Jean-Michel Basquiat's "In Italian." © The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat/ADAGP, Paris, ARS, New York 2013

A detail of Jean-Michel Basquiat's "In Italian." © The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat/ADAGP, Paris, ARS, New York 2013

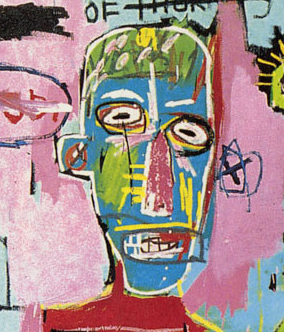

The main character of "In Italian" -- a blue headed figure on the right panel -- seems to stand for some kind of Christ as he might have appeared in a Baroque painting. After all, the phrase "CROWN OF THORNS" is printed above his cranium, with "THORNS" crossed out. The words SANGRE (Spanish for blood) and CORPUS© (Latin for body) are among other words and markings that appear on the figure's body, seemingly added up by a yellow cross that might be a plus sign which turns them into some sort of equation. Christ-like figures with floating crowns of thorns and African features make notable appearances in other Basquiat works.

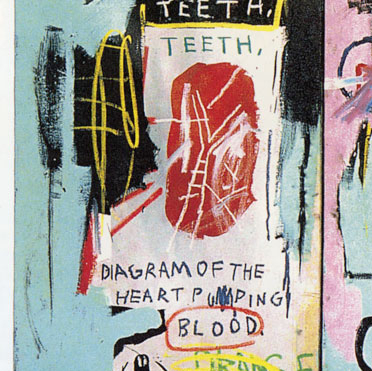

In the left panel, the carefully labeled "DIAGRAM OF THE HEART PUMPING BLOOD" might be a reference to the "Sacred Heart," a symbolic representation of Christ's love for humanity, and also an emblem for many Roman Catholic institutions. It should be mentioned that although Jean did attend a Catholic high school -- where religious images must have made an impression -- he used religious imagery in a free-wheeling and personal way, hybridizing and personalizing European and African forms and rites.

A detail of Jean-Michel Basquiat's "In Italian." © The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat/ADAGP, Paris, ARS, New York 2013

A detail of Jean-Michel Basquiat's "In Italian." © The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat/ADAGP, Paris, ARS, New York 2013

A Baroque image of the "Sacred Heart"

A Baroque image of the "Sacred Heart"

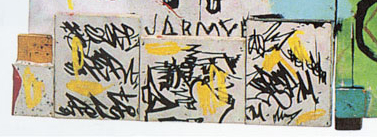

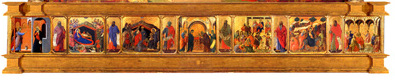

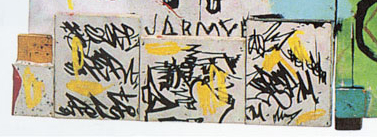

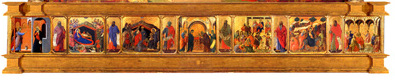

Those familiar with Basquiat's life story will also recognize that the heart diagram was likely recalled from Jean's early study of the book "Gray's Anatomy," which he read with morbid curiosity while recovering from being struck by a car when he was very young. And as it turns out, the "Christ" figure actually began as a portrait of Basquiat's friend and studio assistant Stephen Torton, who later recalled that Jean added the "CROWN OF THORNS" inscription after the two of them fought over a woman. One of the interesting aspects of "In Italian" is that it is, to some degree, a collaboration. Stephen Torton made its distinctive criss-crossed stretcher bars, and a graffiti artist known as "A1" made the group of small attached canvases that Basquiat biographer Eric Fretz says are like the small panels often found on the "predella" (platform) of an altarpiece.

A detail of Jean-Michel Basquiat's "In Italian." © The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat/ADAGP, Paris, ARS, New York 2013

A detail of Jean-Michel Basquiat's "In Italian." © The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat/ADAGP, Paris, ARS, New York 2013

The predella of Duccio's "Maesta" Altarpiece, (1308-11)

The predella of Duccio's "Maesta" Altarpiece, (1308-11)

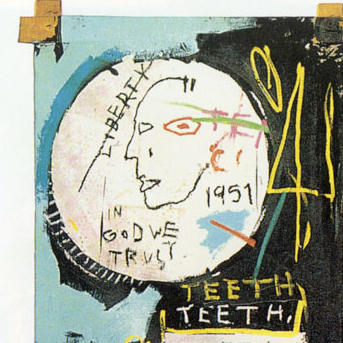

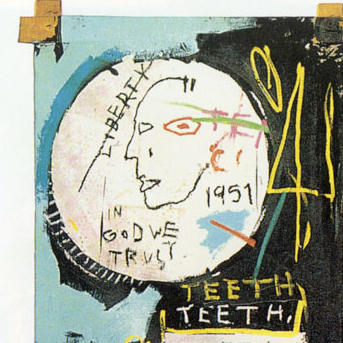

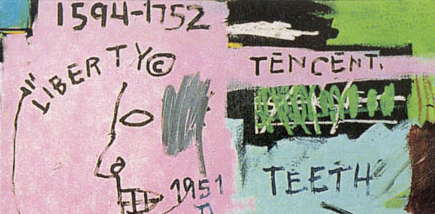

Added to this Voudou/Catholic mix of esoterica are two images of Washington quarters, both dated 1951. Is it possible that the year 1951 refers to the beginnings of the American Civil Rights movement? It was, after all, the year that the father of an 8-year-old African-American sued the Kansas State School Board so that his daughter could attend an all-white school. That may or may not be the case, but in the left panel of "In Italian" LIBERTY is suspiciously crossed out and "IN GOD WE TRUST" is reduced to a sarcastic scrawl. Also, George Washington's right eye stares directly at the viewer, giving gallery-goers the creepymirada fuerte(strong glance) found in many Picasso portraits. The quarter on the right panel has been succinctly de-valued with the text "TEN CENTS." A forever de-contextualized date range -- 1594-1752 -- floats above.

A detail of Jean-Michel Basquiat's "In Italian." © The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat/ADAGP, Paris, ARS, New York 2013

A detail of Jean-Michel Basquiat's "In Italian." © The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat/ADAGP, Paris, ARS, New York 2013

A 1951 Washington Quarter

A 1951 Washington Quarter

A detail of Jean-Michel Basquiat's "In Italian." © The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat/ADAGP, Paris, ARS, New York 2013

A detail of Jean-Michel Basquiat's "In Italian." © The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat/ADAGP, Paris, ARS, New York 2013

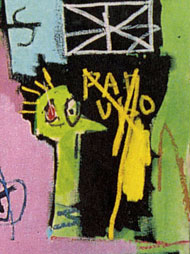

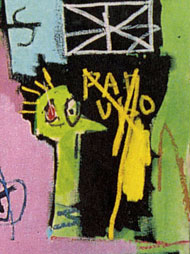

Despite the rich multiplicity of themes suggested by the words, dates and images of "In Italian," any effort to bring order to them is ultimately be doomed to frustration. Basquiat was a cultural and aesthetic channel-surfer whose sources are astonishingly diverse and disparate. His texts and images multiply uncertainty, and only Jean might have been able to tell us why he included the word "TEETH" four times, or whether the manic, Pinnochio-nosed green head on the right panel is meant to represent the apostle PAULO (Paul).

A detail of Jean-Michel Basquiat's "In Italian." © The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat/ADAGP, Paris, ARS, New York 2013

A detail of Jean-Michel Basquiat's "In Italian." © The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat/ADAGP, Paris, ARS, New York 2013

Puzzling out Jean's meanings is an engaging game, but "In Italian" was never meant to be translated. Jean's best works manage to pull off a balancing act: they mix references, cultures and images with conviction, but elude coherence. Does "In Italian" have things to say about racism? Very likely, yes. Does it subvert religion, culture and language to make a personal moralistic statement? Probably. Can it be assigned a fixed message? No.

The best way to understand "In Italian" is to keep in mind what Basquiat once said about his art in general: "It's about 80 percent anger."

I'd say the other 20 percent is about mystery.

JEAN-MICHEL BASQUIAT

February 7 - April 6, 2013

Gagosian Gallery

555 West 24th Street

New York, NY 10011

.jpg)